Every solo-indie game is a "Palais Idéal"

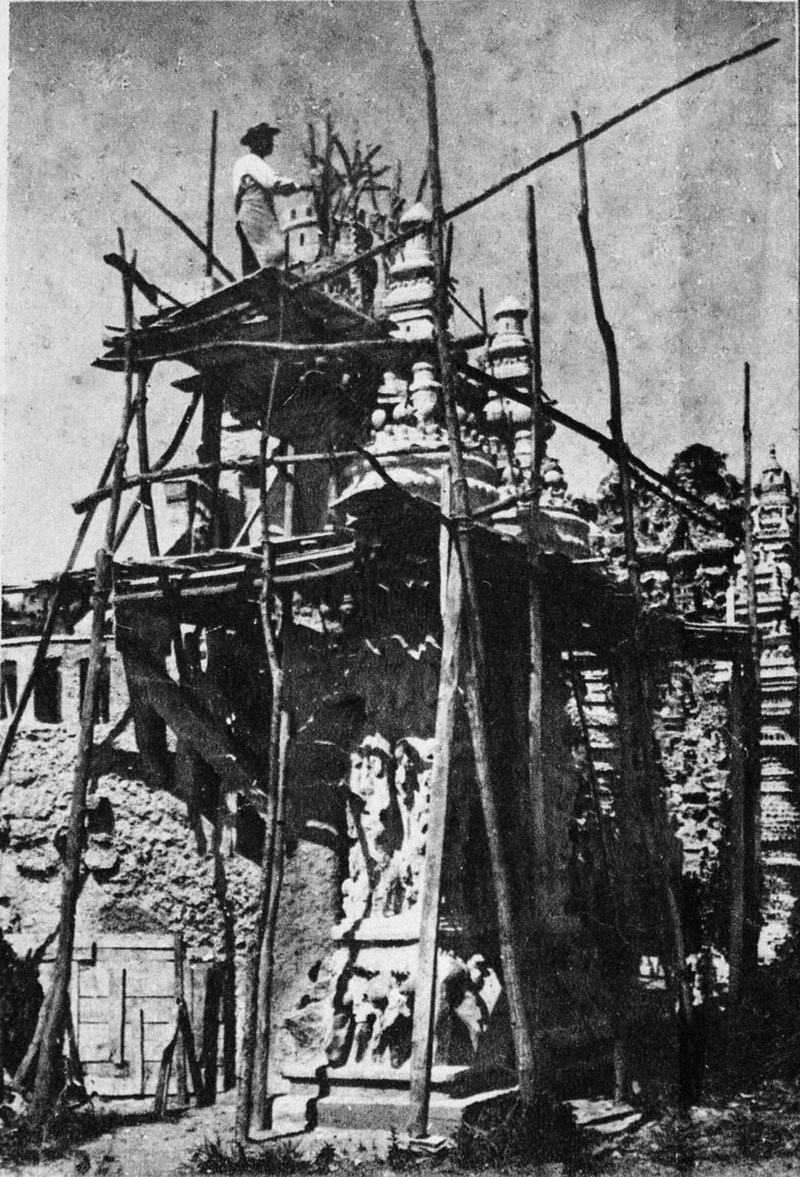

A few days ago, I was reminded of the ‘Palais Idéal’ (Ideal Palace in English), an extraordinary structure in southern France. This sculpture, measuring 12 by 26 meters and built from stone, was the life’s work of a single man.

It began in 1872 when Ferdinand Cheval, a local mailman, was inspired by a stone he stumbled upon during his postal round. This man who had spent his life in poverty, in this very rural France, had found in a stone a beauty that convinced him to begin this mission of a “giant”, as he wrote. Indeed, the walls of his palace also feature numerous inscriptions. In them, he describes his work, insisting on work, nothingness and matter, life, and deaths, and even his own end. He spent 33 years building this edifice, saw his own daughter die when he was already a widower, and dedicated a house in her honor. Then, for a further 8 years, he finally built his tomb, only to die 2 years later. Aside from the tragic and insane dimension of this story, the sheer size of such a task, undertaken alone, reminded me of certain projects carried out by solo game developers.

Of course, these stories differ in countless ways from that of the Facteur Cheval 1, but there are echoes in all these projects, which were the story of one man, or one woman, who brings his vision to bear with the sweat of his brow, over the course of days, seasons and years, in a project whose scale sometimes boggles the mind. There may also be echoes in the motivation behind such a quest. To build something that will outlive us, all the more so for video games as they will be played by others, sometimes thousands of strangers. Building something of our own, for ourselves too, because these games, like this sculpture and this tomb, are also sometimes refuges.

Let’s take a look at some of the stories of those who have succeeded in bringing their vision to this art form, so complex and plural, that is video games.

1 “Facteur” being the french for “mailman”, his work would later be called ‘Le Palais Idéal du Facteur Cheval”.

The first example that comes to mind is that of Tarn Adams, creator of the immense Dwarf Fortress. He began development in 2002, and in over twenty years created the most profound gameplay, in the sense of raw complexity, of raw contingence , ever created. The singularity of this game led to its entry into the MoMA, an exceptional feat for the video game medium, in 2012. How ironic that such feats were achieved by a single man rather than a studio of 300.

DF inspired Rimworld, which is not a one-man project per se, but nonetheless created and led by Tynan Sylvester, who has been developing the game since 2012.

Another well-known example of a solo project is Undertale, a landmark game and work in its own right. Just as Ferdinand Cheval wasn’t a sculptor or architect, Toby Fox wasn’t a developer by training. He started composing music at a young age, which I imagine enabled him to produce a quality soundtrack for Undertale, and was certainly a factor in its success. Gamedev requires knowledge, often advanced, of fields that originally had little to do with each other, music and art – asset creation – being among them.

Tarn Adams is a mathematician by training. This probably makes it easier to learn how to program, and also explains how one man could create the logical mechanisms that enable systems as complex as those in DF. After all, many things lead to the creation of video games and it’s fortunate that the Internet has made this accessible to so many.

I should also mention one particular developer in that he developed his game while working as a security guard. Chris Hunt began working on Kenshi in 2006. He later quit his part-time job to concentrate on this very special game, and finally released the game 12 years later, in 2018. Kenshi is a unique game, as much for its environment, lore and graphics as for its mechanics. In it, the player leads a squad of one or more characters, evolving in a post-apocalyptic world on a rather distant scale, suited to this sandbox style. The player character is thrown into the world for no apparent reason or story, with no significant advantage over NPCs, capable of a total freedom matched only by his or her vulnerability and, of course, the range of possibilities.

More famously, the farm-village RPG Stardew Valley, developed by Eric Barone, also known as ConcernedApe, took “only” 5 years to complete.

Of course, we must also mention what is, in my opinion, one of the greatest games, if not the greatest, which was originally developed by a single man: Minecraft. Of course, Notch surrounded himself with his game, then stepped back to let what became Mojang continue working on it.

All these development times, ranging from 5 (often considered the time required for a solo gamedev) to more than 20 years, are proof on the one hand of the intrinsic difficulty of creating a game with two hands, and on the other of the ability to persevere in the creation of a single work.

What strikes me after listing these games is that many of them share what have been called “sandbox” systems. These are indeed my favorite games, and so it’s probably a bias that explains my choices. However, these games are still the ones that usually come up when we talk about solo gamedev. I believe there’s a link between these permissive, open-ended mechanics and the very fact of creating a “giant” work of art. By definition, for an open game to be interesting, you have to work on it absolutely extensively, which has an exponential cost in terms of time, like everything else in IT. This depth also implies depth in the algorithms (DF or Minecraft are not trivial games to program, to say the least).

Symmetrically, games with simpler systems such as Undertale are striking for reasons that bring them closer to other mediums such as literature, film and, of course, music, without of course detracting from the genius of certain Undertale mechanics such as open turn-based combat mixed with interactive dialogues.

Whatever the nature of their depth and complexity, these seminal games are above all the finished realization, in countless endeavors, of one man’s vision. And it is perhaps this advantage, in the fact that it is a Herculean but personal and therefore singular task, that lies behind the quality of these games created by one and the same person.